In 1808 the old Covent Garden Theatre burned to the

ground. Although this is slightly outside the time period of the Venus Squared

series of novels, I was so taken by this description of that event I’ve posted

it here, in its entirety. In 1810 a new theatre was opened on the site of the old one. The 'new' theatre also suffered at the hands of a fire, burning down 1856. If you want to know what happened to it, well, it's where the Opera House is today.

.

.

The Covent Garden Journal by John Joseph Stockdale, Report

dated April 28th 1810 – for George, the Earl of Dartmouth

THIS noble building, which was built in the year

1733, and enlarged, with considerable alterations, in 1792, was, on the morning

of the 20th September, 1808, reduced, by a most tremendous conflagration, to a

heap of shapeless ruins. The performance of the preceding night was Pizarro, a

spectacle wherein all the creative powers of the machinists and decorators had

been exhausted at both the theatres. It is supposed, that the melancholy

catastrophe occurred in consequence of the wadding from a gun (fired in course

of the performance) having lodged in some part of the scenery, which the prying

eye of the strictest investigator, could not possibly have provided for. The

portrait of Cervantes was the afterpiece, and both performances were received

with eclat by a crowded and elegant audience.

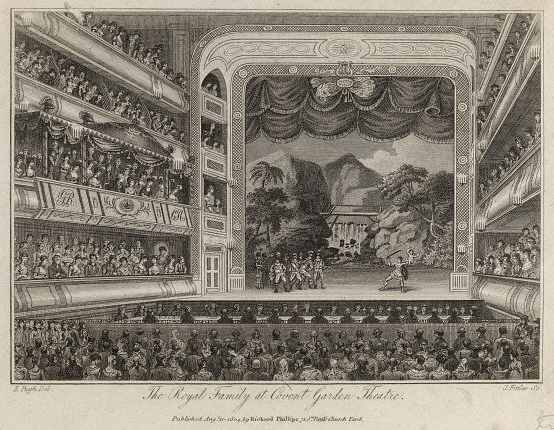

Inside the old theatre - circa 1804

During the representation, which was over by eleven

o'clock, nothing transpired indicative, in the least degree, of the mournful

sequel. About twelve, Mr. Brandon paid his usual visit of circumspection to all

parts of the house, and, conceiving that everything was perfectly secure,

retired shortly after to rest. The same unsuspected tranquillity prevailed at

two o'clock in the morning, at which time the watchman sedulously "paid

his sober round" and discovered nought whereon to ground alarm. About

four, however, a poor frail sister of the Cyprian band perceived the flames

bursting forth with concentrated impetuosity, and communicating her terrific

tale to the guardian of the night, the latter instantly called up Mr. Brandon.

Now a dense volume of smoke, and, shortly after,

wreathed columns of flame, were seen to issue from the ventilator, on the

topmost part of the roof. Within the space of ten minutes, this portion of the

building was, distinctly, observed on fire in different parts; and, in half an

hour, the whole edifice presented to the view a fiery furnace, from which the

flaming pillars rose, forming, in the most awful style of destructive elemental

architecture, a truly worthy temple of the sun. Though it was then broad day,

so intense and furious was the conflagration, that it was perceivable in many

of the most distant environs of the metropolis. The alarm became universal. The

engines of every fire-office in town, and of all the adjacent parishes,

rattling through the streets, with busy din, awakened the inhabitants to the

view of this scene, which rivalled, in ruddy splendour, the glory of the

opening day.

Thousands presented themselves before the theatre,

eager to manifest their zeal in arresting the baleful progress of the raging

element. In vain; — for, the houses, which so deeply surrounded the building on

every side, prevented the ardour of exertion from being attended with success.

The roof fell in about six o'clock ; and, so unexampled was the progress of the

consuming invader, that, before eight, the whole interior of this splendid building,

audience-part, stage, different entrances, treasury, music-room, &c. were

totally annihilated.

The Remains of the Old Covent Garden Theatre after the fire 1808

Perhaps there is no recorded instance of so complete

a destruction, of similar extent, in so short a space of time. Every composite

material of the building was, however, fuel to the fire, and the large area

served to ventilate it to that unsubdued pitch at which it had arrived. All

hopes of rendering service in this quarter be coming now unavailing, the

firemen directed their efforts to prevent the increase of the calamity, as the

houses which squared about the theatre were manifestly endangered. Owing to

their height, it was found impracticable for the engines to play over them;

but, the leather pipes being conveyed up the stair-cases to the third floors,

and their ends being thrown down and fastened to the engines below, an

ingenious facility of effective action was contrived. Nothing, however, could

prevent the communication of the flames with the houses in Bow-Street, to which

side the "Malus Auster" had an unfriendly inclination. Several of

them were connected with the theatre, by a respective appropriation to different

parts of the establishment. They, with some others, became victims to the manes

of the mother-edifice.

The fire raged with more violence at the eastern side

of the upper part of Bow-Street, where the house, No. 9, belonging to Mr.

Paget; Nos. 10 and 11, attached to the theatre; No. 12, belonging to Mr. Hill;

No. 13, the Strugglers Coffee - House, wherein Mr. Donne lost almost his whole

property ; No. 14, belonging to Mr. Johnson, the fruiterer; and No. 15, the house

of Mr. M'Kinlay, a book-binder ; were all completely destroyed, and scarcely

" left a wreck behind." The three latter houses, with the exception

of Mr. Donne's part of the property, were insured in the Hope, for, £2650. Some

of the others were entirely uninsured, and some only partially so. Nos. 16 and

17, in the same street, were seriously damaged. In Hart-Street, four houses

opposite to the theatre attracted this firey magnet at the same instant, and

were only, by the greatest activity on the part of the firemen, secured from

farther damage than a severe scorching.

The " proximus ardet Ucalegon," and the

" tua res agitur," were promptly attended to with respect to

Drury-Lane Theatre, which, it was apprehended, from the number of flakes

carried thither by the wind, would share in the sacrifice to the god of fire,

and receive the Salmonean punishment for a priority, in imitative effects, to

outshine the enraged deity. A great number of people had mounted the roof of

the Theatre of Drury-lane, in order to open the large cistern of water there in

case of necessity. The windows of that building were also stopped with wet

cloths, to prevent the entrance of the flames, — a precaution by no means

unnecessary. All the people in the immediate vicinage kept their servants

employed on their respective roofs to pick up the flakes of fire as they

dropped on them.

This has been the whole extent of injury sustained in

the neighbourhood; but as to the theatre itself, it wa6 totally consumed; and

even the walls on the Hart-street side were not left standing. In that angle of

the edifice, the Ship- tavern and part of Mr. Brandon's, the box-keeper's,

office, are the only remains. The amount of the insurances did not exceed

60,000/. and the savings from the Shakespeare premises amounted to about 3500/.

the entire being but one-fourth of the sum necessary to replace the great loss

sustained. In addition to the usual scenic stock was a great quantity of beautiful

new scenery for a melodrama which was to be shortly forthcoming.

Of the original pieces of music of Handel, Arne, and

many other celebrated composers, no copies had been taken; and of many others,

which had also been destroyed, only an outline had been given. Several capital

dramatic productions, the property of the theatre, were for ever lost. The

organ, left by Handel as a bequest to the theatre, which was valued at 1000

guineas, and never played but during the Oratorios, was likewise consumed. Mr.

Ware, the leader of the band, lost a violin worth 300/. which for the first

time in ten years he had left behind him. Mr. Munden's wardrobe, which cannot

be replaced under 300/. shared the general fate; as did Miss Bolton's jewels,

and other performers' property, in the aggregate amounting to a very

considerable sum.

We now come to the most painful part of the

narration, — the dreadful havoc committed on human life by the falling of the

burning roof. At an early stage of the fire, the great door under the piazza in

Covent-garden was broken open by a party of firemen, and an engine belonging to

the Phoenix fire-office, being introduced within the passage, was directed

towards the galleries where the flames raged most fiercely : horrid to relate,

the burning roof of that same passage, in which they were, fell in with a tremendous

crash, burying the unhappy and too daring firemen, with others who had rushed

in along with them, under its ruins. A considerable time elapsed before the

rubbish, which now obstructed the doors of this fatal pas sage, could be

removed. When effected, a scene of horror was presented to the view. The mangled

bodies of dead and dying appeared through the rubbish, or were discovered in

each advance to remove it. At twelve o'clock that day, eleven dead bodies had

been carried into the church-yard of St. Paul's, Covent-garden. Some miserably

mangled creatures, with broken limbs and dreadful bruises, were conveyed to St.

Bartholomew's, and some to the Middlesex, hospital. It would shock humanity to

draw a faithful picture of the situation of those wretched persons who were dug

out of the ruins alive; they were, in general, so much burned as scarcely to be

re cognized by their nearest relatives; and in many instances their flesh was

literally peeled from the bones. The dead bodies taken from the same place were

nearly shapeless trunks. The strictest examination, for the purposes of

identity, was vain, in those who came to claim the "sine nomine

corpus." The coroners for London, Middlesex, and Surrey, sat on 19 bodies

destroyed at the fire; viz. 12 at Covent-garden, 3 at St. Bartholomew's, 2 at

the Middlesex- hospital, and 2 at St. Thomas's.

Many persons were conveyed, in the most hope less

situation, to their own houses. The waste of human life, on this lamentable

occasion, falls not short of thirty persons. From the evidence of William

Addicote, one of the stage-carpenters of the theatre, and William Darley, one

of the firemen belonging to the Eagle Insurance-Office, and one of the jury, an

eye-witness of the falling in of that ceiling by which the unfortunate men were

burnt to death, — it appeared that the firemen and others who perished had been

employed in endeavouring to extinguish the flames at the room called the

Apollo, which had fallen in upon them. The surmises with respect to barrels of

gun-powder having exploded were proved to be unfounded, no more of that article

being ever kept in the house than was sufficient for the consumption of a

single night.

On the next day, another Victim was added to the

list, by the fall of the wall in Hart-street; several others were bruised

severely, though they had all been warned of their danger to no purpose. The

names of the deceased sufferers, as well as could be collected, are: — Mr. T.

Harris, jun. Mr. R. Davis Musket William Ricklesworth George Kilby John Seyers

James Stewart Samuel Stevens Richard Cadger T. Holmes James Hunt William Jones

James Evans J. Crabb T. Mead T. James Richard Rushton Mr. Hewitt J. Beaumont

Richard Bird James Philkins John Oakley Optician,of Hydcstreet,Blooms- bury,

Serjeant of the Bloomsbury Volunteers. A Gentleman lately from Wales to London

on a visit. Firemen belonging to Phoenix-Office.

Begging after the fire

Another person, a private in the guards, was taken to

the Military Hospital, where he died in three or four hours. These were the

names as nearly as could be gathered. Several were still missing. Mr. Richards,

clerk to Messrs. Shaw and Edwards, St. Paul's Church-yard, was so dreadfully

scalded by the water falling from the burning materials, that he died about 12

o'clock the same day. The firemen and others were employed for some days in

pulling down the tottering ruins which threatened destruction to the passengers

in Bow-street. On the following Saturday two more bodies were dug out of the

ruins. The books of accounts, deeds, and the receipt of the preceding night,

were fortunately preserved by the exertion of Mr. Hughes, the treasurer. Though

a considerable number of engines were in constant and prompt attendance, yet,

owing to the main pipe having been cut off with the intend of laying down a new

one, more than an hour elapsed before some of them could be supplied. During

this defect in the supply of water, the neighbours derived the most essential

assistance from the pump of the Bedford Coffee-house and Hotel. The utmost

effect was perceived from the playing of the engines for about an hour, when

all hope was lost by the crash which announced the falling-in of the roof, and

the consequent destruction of the elegant interior.

The Bedford and Piazza Coffee-houses owed their

preservation to a wall, some time since erected for the purpose of insulating

the theatre from the back of these premises. Among the other losses sustained,

the Beef-Steak Club, which held their meetings at the top of the theatre, and

has existed for many years, lost all their stock of old wines, valued at 1500/.

beside their sideboard, and other implements. Pieces of scenery and other

decorations were carried through the air to immense distances. A fragment of

carved wood, all on fire, fell near St. Clement's church, in the Strand. The

figure of Apollo, on the dome of Drury-lane Theatre, was a

strikingly-illuminated object, as the fiery shower fell around it. Great praise

is due to the volunteer corps and the detachments of horse and foot guards who

attended. Several miscreants, taking advantage of the confusion, attempted to

plunder, but were held in custody. The whole property destroyed amounted to

considerably more thau 100,000/. and, at the utmost, was covered by insurance

to the amount of 75,000/. The dark prospect of the proprietors may yet be

cheered by light, but "when shall it shine on the night of the grave?"

A subscription was opened for the relief of the sufferers. The King's Theatre

was very liberally offered to Mr. Harris by Mr. Taylor; and the Covent- garden Harris

by Mr. Taylor; and the Covent- garden Company played there till the

commencement of the Opera-season. The plan of a new theatre on the site of the

old one, to be completely insulated, was ordered and accepted by the

proprietors.

The new theatre built after the fire, pictured in about 1828. This too burned down.

Angela Elliott's book

The Finish, being the first in a four part series about Covent Garden prostitute Kitty Ives can be found

here.